Rethinking urban expressways – World

Interview with Paul Lecroart, IAU Ile-de-France

Paul Lecroart works at the IAU Ile-de-France (Urban Planning & Development Agency for the Paris Region) where he leads a programme on large urban projects and metropolitan strategies in the Paris Region. He is in charge of a study on the impact of the transformation of urban expressways into avenues in North America, Korea and Europe. His fields of interests include transitional public space strategies, landscape patterns and ecomobility.

Paul, you have been working at IAU for quite a few years, observing and making proposals for the Paris Region. When emerged the idea of your research about the transformation of expressways? Is it a current subject for the Paris Region?

It wasn’t, but it has become a current subject. In the last fifteen to twenty years we worked a lot on public transport, trying to imagine and implement a public transport system for the Paris region and we developed the Grand Paris Express network. But we hadn’t worked much on roads. Obviously roads are very important for traffic, but also for the organisation of the city and its urban structure. When I heard about some projects of expressway removal in the USA, I thought it was an interesting subject for us, because we don’t know what to do with the some of our expressways. Maybe there could be something more interesting then just to leave them as there are. Expressways in cities are problems of disconnections, of going from one neighbourhood to another. They tend to segregate cities, segregate traffic, segregate functions, and so maybe we could combine traffic with the city and to create mix use public space.

Expressways are monofunctional transport spaces ignoring the surrounding neighbourhood. How did their removal impacted the surrounding neighbourhood? And where went the traffic?

I think that is the most central question, at least for traffic engineers and elected officials. They always worry about where the traffic is going. But when you create public transport, you usually have more passengers than planed before. The same happens with the road. If you built a road, you have traffic that didn’t exist before. What happens when you remove an expressway and you transform it into a boulevard? You reduce speed, you reduce capacities and you create connexions. And so the environment change, the people decide not to take the car and you have less car traffic after then you had before. You have more pedestrian traffic, more bicycle traffic, more public transport traffic. Some people change their behaviours and they decide to shop in their neighbourhood and not ten kilometres away from home. People change their behaviour, so maybe we don’t need many expressways, but more streets for people to walk, to meet, to make the economy work.

In your case studies, is there an example that particularly impressed you by the changes happening to the neighbourhood after the deconstruction of the expressway?

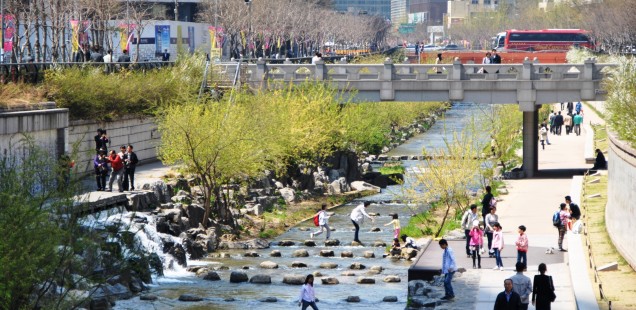

I’m very impressed by what happened with the Cheonggyecheon Expressway in Seoul in Korea. There used to be an expressway crossing the city centre and it carried almost as much traffic as the Boulevard Périphérique in Paris. After a lot of discussions they decided to revive the river, which was hidden under the expressway, and to deconstruct it. There used to be four lanes for the higher speed traffic and ten lanes for the lower speed traffic. These ten lanes were reduced to four lanes and the traffic is still smooth today. Why is that? Because people change behaviour and they find other ways of getting into town, other ways of living the life in a city centre, then using your car for short distances. In the Paris region about 60% of all car traffic is for trips of less than 5 kilometres, which could easily be made differently.

Stakeholder support seems to be essential in these urban transformation projects. Were the projects supported by the local actors or did there remain a strong opposition?

That is really important, but it depends on who starts the discussion and who is in charge of the expressway. In some cases it’s the state, in some cases it’s the city and the results are very different. For instance in New York there was the West Side Expressway of Manhattan. It was an elevated expressway that collapsed in the seventies. The State of New York wanted to build a tunnel for a new expressway and this started a big discussion. After 15 years of failed discussions, the city of New York took the project in charge. As the city is less interested in cars then in city life, they realised that it was more important to give value to this area, which was abandoned, and to create a new waterfront with housing, businesses, parks and to open the waterfront to the people. The idea is that you can combine the traffic with the city under some conditions. The conditions are to have city life and a lot of pedestrian movements on both side that already creates a city environment and not an expressway environment.

Do you know cases where there have been protests against the expressway removal?

In the case of the West Side Highway in New York, the local communities fought against the Westway tunnel project of the state and that is why it had been finally abandoned. In the Sheridan Expressway project, the communities are also pushing to remove the highway. In Seoul the conflicts where about the future of the street vendors, as there were many street vendors selling electronics and hardware underneath the elevated expressway and the city of Seoul wanted to remove them. So it was not against the transformation process, but about the integration of the small businesses. In San Francisco, the Central Freeway removal project went through two referendums before it was adopted. I did not encountered protest against the removal of expressway, but there is always a strong debate. Usually the business communities and the car drivers are for keeping the expressway and local residents want the streets for other functions.

The economic crisis has reduced the investment capacity of many public authorities. Today they hesitate before investing in a new urban project. Did these projects need a strong financial support?

You need to think long term, but to start with the cheaper actions in the short time. The idea of redesigning expressway is to create more value for the neighbourhood, so this value, if you manage to capture it, can produce resources for these cities to help finance the development of the boulevards. That’s what happens with the Embarcadero Freeway in San Francisco. There was an important urban development, where they used to be the expressway interchanges, and so by reducing the road width you gain land on both sides that helps to finance projects. But you need to go slowly in this process, because you can’t work on ten kilometres of expressway in one go. It really is too difficult.

You need to start with strategic small scale projects. For instance the mayor of Paris didn’t work on the whole of the banks of the river Seine, but first on a small part of the centre in Paris, and it’s the same in San Francisco. You work on small parts and maybe you can have some hybrid projects, like for instance the Sheridan Expressway in the Bronx in New York. They just transformed what is easy to transform and left the difficult part, where the expressway goes below ground, for later. By creating new intersections on expressways, you can already develop the land on both sides which then gives you resources to go on. And the land is often in public ownership, as it’s on the right of way of the expressway. It was bought by the public authorities in case they wanted to enlarge the expressway.

You worked on twelve case studies situated mostly in North America and in Asia. Did you identified similar projects in other regions?

It is interesting to understand why this movement started in America. It started there, because the US urban expressway network was built 20 years before ours in Europe. This infrastructure is now aging, weakened by wear and tear and sometimes by poor maintance. They now need to reinvest in them and in fact in the American cases the financial reason is why they are removing them. There would cost so much to reinforce, to retrofit with the seismic devices in places where are earthquakes, that it’s much cheaper to have an urban boulevard than to have an elevated expressway. In San Francisco or in Vancouver or even in New York the main reason to deconstruct the expressways is long term financial investments.

In Europe, things are a little bit different because we don’t have so many urban expressways. Some cities don’t have them at all and there aren’t so intrusive. But I have identified other places. In the Paris region we have six projects of removing expressways. In Birmingham they got rid of the southern and eastern part of the innercity ring road, nicknamed the “Concrete Collar”, with a positive impact on the opening up of new development potential for the extension of the City Center regeneration and Eastside redevelopment. In Luxemburg City transforming an urban expressway in a boulevard has allowed the Kirchberg Plateau to redevelop successfully around the EU Commission headquarters.

And in some other countries like in Japan, Tokyo, they are thinking of getting rid of an expressway which is built on top of the river, the Nihonbashi expressway. In San Paulo, Brazil, there is also discussion about the idea of deconstructing the Minhocao. One of the issues now in the rapidly developing metropolises world-wide is to make decision-makers understand that they may be ruining their cities by building extensive urban expressway networks and flyovers on top of every crossroad. So it’s becoming a real movement and in the next ten years we might see more and more of these projects.

The City of Paris is encircled by its Boulevard Périphérique since the 1960s. The municipality covered smaller parts of this expressway to improve the links with the outskirts. Is covering the right approach?

That is a big question of course. It is not only spatial, but also institutional, as the Périphérique is the administrative limit of the town of Paris, and it is also symbolic for the relationship between Paris and the suburbs. For the moment the idea is to further reduce the traffic, as it has gone down a lot in the past 10 years. And maybe set up public transport on the expressway.

Today, if you propose to connect neighbourhoods and to develop land on both sides of the Périphérique most of the elected official will say that you have to you have to go on covering it. But you can’t cover the whole ring road for technical and financial reasons. Covering is not a long term solution, it doesn’t change anything on traffic, and it doesn’t change the greenhouse gas emissions or the heat island effect.

Maybe having a kind of green boulevard around the city of Paris could be an important change and also an interesting experiment for Paris to do something that no city has done on this scale. Maybe it’s a project for the next forty years. The value of this open space is interesting. Many architects had been asked to work on building on top or around the Périphérique with quite dense urban forms. But maybe we can also open land, open views and keep this fantastic ring as an open space for Paris.

You will soon publish the following case studies after these of New York, San Francisco, Portland, Vancouver and Seoul? Do you already have new challenges in mind?

The next steps are to summarize the lessons learned from these studies and to elaborate the most interesting point for the Paris region. Second is to monitor what is happening in the Paris Region as there are projects and to take part in the discussion. For example, next week is going to be the final presentation for the work on the A4 motorway. What I hope is that we can create a movement with different actors to start discussing more broadly on these issues. Do we need expressways inside the A86, the second ring road after the Périphérique, and how can we work together on a project to transform the expressways in urban boulevards?

One of the ideas is that expressways prevent connections and that is what is valuable for a city. If you can’t connect two neighbourhoods they might as well be forty kilometres apart. If we connect we can create value that can help to build housing, we got very strong need for housing in the Paris region, and we got needs for public spaces, green areas, the right places to have jobs and activities. So maybe these projects can be developed along these future urban boulevards.

Author: Christian Horn is the head of the architecture and urban planning office RETHINK in Paris, France