The Japanese railway stations, a model for the Grand Paris ? – France

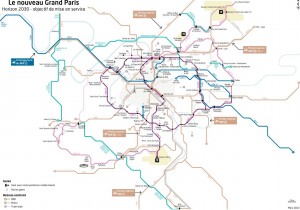

The Grand Paris transport network © Société du Grand Paris

Since 2008 a new project for the greater metropolitan area of Paris, called the Grand Paris, emerged. Structured by a new major public transport network, the aim of the project is to connect the important existing and future urban centres, to cover a large territory and favour the construction of housing, offices and the creation of jobs.

This objective of revitalizing the metropolitan area should be reached by the construction of a new automatic metro network with 72 new stations on 4 lines all over the territory. Almost 90% of the population will be living at no more than two kilometres from a station[i], that should act as new urban centres.

“Integrated into their environment, stations will be a place of life for both, passengers and residents of surrounding areas, as well as generators of new dynamics for the compact and sustainable city of Grand Paris»[ii].

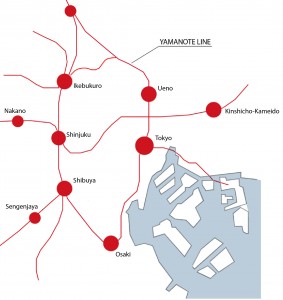

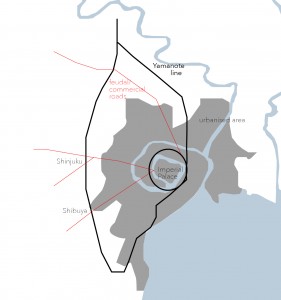

The Yamanote line in Tokyo © Marija PAVISIC 2015

One of the main references for this ambitious project is the Yamanote Line in the city of Tokyo[iii], a key example of urbanisation around transport stations. Indeed, Tokyo’s stations are much more than just the crossing of transport flux. They form the centres of their neighbourhoods and shape the city. This unique relationship was described by Roland Barthes in his book Empire of Signs, published in 1970:

“If the neighbourhood is quite limited, dense, contained, terminated beneath its name, it is because it has a centre, but this centre is spiritually empty: usually it is a station. The station, a vast organism which houses the big trains, the urban trains, the subway, a department store, and a whole underground commerce – the station gives the district this landmark which, according to certain city planners, permits the city to signify, to be read. The Japanese station is crossed by a thousand functional trajectories, from the journey to the purchase, from the garment to food: a train can open onto a shoe stall.“[iv]

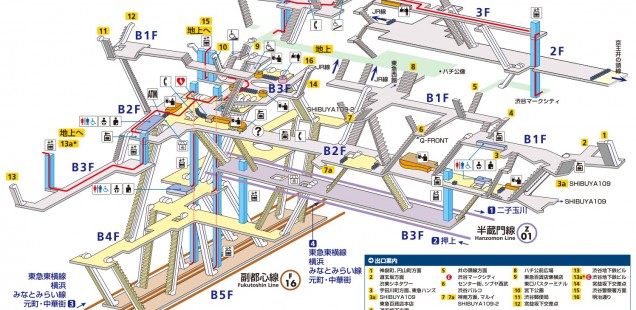

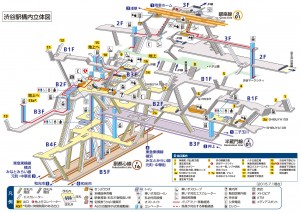

Map of Shibuya station on the Yamanote line in Tokyo © Tokyo Metro

It is true that Japanese stations accumulate many kinds of functions other that the transport, such as leisure, commerce, restaurants. The station becomes a cultural image of the society, a landmark in the city. This concept was brought even further by developing a special term into Japanese urban planning culture, “eki-mae”, which literally means ‘in front of the station’. It designates the development of many kinds of functions around stations, reinforcing the central image of their buildings.

How come that this way of structuring the urban development through transport stations emerged a long time ago in Japan, while in our European cities it is still being questioned? Can it be taken as a model for the future urban development of the European cities?

The Yamanote line in Tokyo © Marija PAVISIC 2015

It is important to take into consideration that Tokyo’s railways companies are private companies, and this since the beginning of the densification around the stations. In fact, it was precisely the privatisation of the Japanese National Railways (JNR) company in 1960s that encouraged this concept to develop. At that time the public JNR started facing economic difficulties. In order to continue to strengthen the offer in transport, the national company went private. To provide the necessary additional income, commercial activities attached to the station were allowed and encouraged. The raising importance of these transport hubs finally led to bigger land value around and to the densification and diversification of uses around those transport hubs.

Secondly, at the time when the Yamanote Line was built, it mostly ran across non-urbanised areas and crossed main roads leading to other major cities, such as Kyoto. The stations on these crossing points experienced a radial development around and are nowadays known as major centres such as Shinjuku and Shibuya.

Thirdly, the efficiency, punctuality, speed and cleanliness of Tokyo’s and Japanese railway infrastructures led to a great number of citizens (60% of 13,22 million inhabitants of Tokyo metropolitan area) preferring trains rather than any other means of transport. In order to keep it that way, the stations need to catch up constantly with latest trends and offer services for all kinds of users.

Subway and other urban rail services in Tokyo © UrbanRail.Net

Based on this analysis, it is hard to predict if the model of Tokyo transport stations might be fully applied in the case of France and the Grand Paris. Generally the French population is attached to its public services and a complete privatisation of the public transport is not imaginable at the moment. Public transport is seen as an important tool of social mixture and access to the territory and for this transport prices must stay affordable for all citizens. But recent renovations of national rail stations in France are turned towards the combination of transport and commerce, as the only adjacent function. They seem to be led by the same model of developing additional income, but it is uncertain that the only function of commerce might be sufficient for a strong urban development around the stations of the future metro network. Today the rail network of the Paris metropolitan area is not as developed as the one of Tokyo. The Grand Paris metro network should change this and parts of the new lines are planned to connect less developed suburban territories with dense urban poles like the business district of La Defense. This should in theory led to a densification and intensification of these areas and favour the construction of housing, offices and the creation of jobs. In terms of efficiency, punctuality, speed and cleanliness, according to the company the ‘Société du Grand Paris’, in charge of the realization of the project, the Parisian railway service is today a synonym of discomfort, delays and stress[v]. And this is easy to confirm by on site experience. As such it does not represent yet a real comfortable alternative to other means of mobility, like personal cars.

It is clear that Grand Paris should not simply replicate the Japanese model of urban development around transport stations. But at the present time the Parisian public transport network and its services are not satisfactorily developed and cannot satisfy the everyday needs of a metropolitan area of 12 million inhabitants. So a closer look on this model of urban development is important.

Remains the question, if a major new infrastructure project, like the Grand Paris metro network, is the first necessary step, it will absorb large parts of the regional and national budget for transport, leaving less possibility for investments in more localised mobility projects. Wouldn’t it be the better to modernise the existing transport systems first? Offering a satisfying network on the existing railway system might be a first step towards improving the current transport services and afterwards a good starting point for future projects.

[i] http://www.ile-de-france.gouv.fr/gdparis/TRANSPORTS-GARES

[ii] http://www.societedugrandparis.fr/focus/des-gares-nouvelle-generation/ambition-architecturale

[iii] http://www.ateliergrandparis.fr/mobilite/documents/Orientations03.pdf

[iv] Empire of Signs, Roland BARTHES, (first published 1970)

[v] http://www.ile-de-france.gouv.fr/gdparis/TRANSPORTS-GARES

Auteur: Marija Pavisic, office rethink