Centre National de la Danse – France

In September 2004, the French Centre National de la Danse (National Dance Center) opened the doors of its « new » headquarters to students, professionals, and the public. Situated in Pantin, a town just northeast of Paris, the rejuvenated 1960s-era building symbolizes a growing cultural interest in the Parisian suburbs.

Since its birth as an institution in 1998, the dance center had been searching for a convenient building that could house its various activities under one roof. The initial desire to construct the new headquarters in Paris was quickly abandoned when that was revealed to be too expensive.

Then began a search for an existing building that could be transformed, that was not too far from the center of Paris, and that had the necessary architectural qualities suitable for the prestigious National Dance Center. The selected building, after a transformation, now stands as an inspiring example of how a building can escape demolition and experience a reincarnation.

In Its Former Life

The first, unlucky life of the building began in the early 1960s, when the progressive communist mayor of Pantin, Jean Lolive, commissioned architect Jacques Kalisz to design a new administration center for the town. The gifted young architect conceived an expressive, sculptural building dominated by exposed concrete. It seemed at the time to be a statement against the coming trend in curtain-wall architecture.

After it was built, however, it was considered — by both the administration and the local population — to be oversized for its context. Ambivalence led to negligence and to the building’s eventual degradation. The steel inside the facade’s prefabricated concrete elements, some of which are only 2.8 inches (7 centimeters) thick, suffered from water infiltration and rusted. Some of the facade elements began to break off. Several floors of the building were abandoned, and in 1996, civic officials decided to close the whole building.

Situated in front of the town hall and along the canal Ourq in the center of Pantin, the concrete monument, an example of the brutalist movement, continued its slow and steady degradation. It became an eyesore for the town, and yet its total demolition, less than 30 years after its inauguration, did not seem appropriate.

Finally, in the late 1990s, a solution arrived when the Ministry of Culture and the mayor of Pantin agreed to marry the old administration building with the homeless National Dance Center and to begin a renovation.

In December 2000, the French architects Claire Guieysse and Antoinette Robain won the competition for the building’s renovation. Today, Guieysse still expresses surprise at how easy it was to fit the new program into the existing structure. She recalls that during the planning phase, it seemed as if the building had been designed from the beginning for a more diverse program than that of an administration center.

Rejuvenation and Rebirth

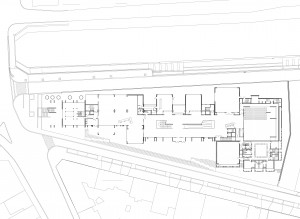

The National Dance Center required 11 dance studios, three of which would be open to the public. The program also called for a library, classrooms, exhibition and conference rooms, a cinema, a cafeteria, and offices. These spaces are distributed over 97,000 square feet (9000 square meters), on four floors of the six-story building. Two floors have not been renovated but have been kept in their previous state for a possible future extension of the program, if and when needed.

The architects renovated the entire exterior and tried to restore the building’s initial appearance. The fragile reinforced concrete elements were repaired and protected through new chemical treatments.

But most of the design work was on the interior. The architects tried to adapt the existing structure to the new program while keeping as much concrete exposed as possible.

They centralized the program around the large, 85-foot- (26-meter-) long entry hall, which stretches up to the sixth floor. This impressive space is dominated by a massive concrete stair and ramp leading gradually to top.

While the original building was completely oriented to the street and closed to the nearby canal on the opposite side, the renovation architects opened the entry hall at several places to the canal and developed a greater transparency. Today, the cafeteria and parts of the reception area are situated behind large glass facades with a view to the water.

The architects designed a red wall for the entry hall, behind the stair and the ramp, which extends to the hall’s full six-floor height. Otherwise, unpigmented, exposed concrete dominates the interior. Aztec-like patterns, which Kalisz cut into the concrete surfaces during the original construction, give a certain aura of mystery.

Because the building had not been originally constructed as a dance center, special attention needed to be given to acoustic insulation. The existing concrete structure promoted sound transmission throughout the building.

To remedy this, each of the 11 dance studios was given a special treatment depending on its situation, configuration, and use. Two of them were conceived as a « box within a box » and completely insulated from the surrounding walls, ceiling, and floor. To reduce the cost of the renovation, the other studios were insulated through their floor structure and, when necessary, also on the ceiling and the walls.

Artistic Finishing Touches

Several artists participated in the renovation project. Hervé Audibert was commissioned to develop the electric lighting concept. He installed several horizontal rows of colored lights that are hidden behind concrete elements. These lights turn on when everyone has left the building, and they have become a sign of the absence of people and the presence of the building itself.

The artist Michelangelo Pistoletto created the furniture for the different areas of the building. Graphic designer Pierre di Sciullo developed the corporate identity of the National Dance Center, including signage and color scheme. The involvement of different artists in the project makes the interior lively and gives it a feeling of completeness.

After 25 years as an office building, the creation of Jacques Kalisz has now undergone a successful renovation and transformation to its next life. The project offers an important lesson. If a building does not perform as expected, perhaps we should see it as a failure of the function, not of the building itself. There could well be a second opportunity to save it from demolition by giving it a new purpose.

Author: Christian Horn is the head of the architecture and urban planning office rethink

Published in « Architecture Week » on the 22th September 2004