La Défense, a unique business district – France

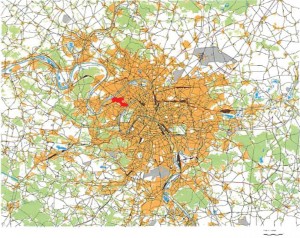

Few urban developments in the Paris metropolitan area have divided opinions as much as the business district of La Défense. Some marvel at La Défense with its collection of high-rise buildings gathered around a large pedestrian plaza, where others see it as a poor sequence of mono-functional office buildings. It is difficult to stay indifferent to this unique site, whose development was driven by an upcoming demand for large office spaces and high-rise buildings in France after the Second World War combined with the wish to maintain the historical skyline of central Paris. Since its creation in 1958, the business district of La Défense has become one of the major economic clusters in the metropolitan area and internationally reknowned. It is served by one of the region’s most intensively used transport hubs and tens of thousands people frequent this district daily, including office workers, residents and visitors. The urban form of La Défense is based on overlaying urban functions, a large elevated pedestrian plaza on the historic axis and a high density through high-rise buildings.

Firmly anchored in its strong relationship with central Paris, La Défense has long been a modern extension or counterpart to the historical centre. Initially little attention was paid to its surrounding territory. The decision of the French state for the construction of La Défense on the territories of the suburban municipalities of Puteaux and Courbevoie lead to important demolitions. A quarter of the territory of Puteaux was demolished to construct the new business district. From that moment on, the further development of this territory was conducted and overshadowed by this economic cluster outside central Paris.

The history and the reasons for the choice

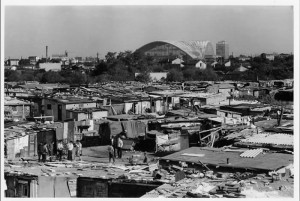

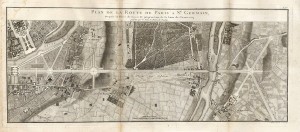

The historical axis of Paris is the main structuring line of Paris’s Western urban fabric and stretches beyond its city limits. Although this axis became distinct through its enlargement in 1667 by André Le Nôtre on the demand of Louise XIV, early Capetian kings already used the path long before to go hunting in the forest of Saint-Germain-en-Laye. Its geographical and historical origin in central Paris was the Pavilion of the Palais des Tuileries, which had been burned down during the Paris Commune in 1871. Few predicted that the territory – after the first crossing of the historical axis over the river Seine outside of the city of Paris – would become the future business district. In the 1950s the area featured mostly detached houses and small factories among small farms, natural areas and several shanty towns in which some 7,000 people lived.

Due to strong economic growth between 1947 and 1973 in France, a period called “The Glorious Thirty », and a fast developing service sector, companys had growing demands for large office spaces that were not available or practical in the historic urban fabric of Paris. Stopped by the Second World War, France wanted to rapidly modernize its cities and to catch up with the new American lifestyle leading towards a consumer society. Modern industrial construction methods developed in reaction to the war damage and a growing population, leading to a period of mass construction of large housing estates on agriculture land. A need for a planning on the metropolitan scale emerged due to the rapid construction, the accelerating growth of the cities and the strong development of the car that dramatically changed the mobility of citizens: between 1954 and 1968, the number of cars increased by 150%.

Around 1950, the French state decided to create an international business district. A state-controlled firm, called EPAD (today named EPADESA), was created in September 1958 to buy the land, build the infrastructure, resell the developed plots and animate and manage the new business district on the municipalities of Courbevoie and Puteaux (today enlarged over parts of Nanterre). This planning operation aimed to gather in one place outside of Paris the new type of high-rise buildings.The idea was to preserve Paris’s historical skyline featuring low-rise buildings and iconic structures such as the Eiffel tower and Sacré-Cœur on the Montmartre hill.

Thoughts about modernising the cities for the needs of modern life and constructing new satellite towns had already emerged before the Second World War. Between 1922 and 1925, the French architect Le Corbusier worked on a plan for the redevelopment of the historic centre, called the Plan Voisin. In this plan broad main roads create a rectangular network offering plots in the city centre for 60-storey high-rise buildings, welcoming 20,000 to 40,000 employees, and residential areas with low-rise buildings organized around green areas. Foreseeing the demand for new typologies of buildings, Le Corbusier wanted to show the possibility of transforming the old centre of Paris into a modern city while preserving the main historic buildings but not the old urban fabric. He thought that the centre should constantly regenerate itself and was opposed to the development of satellite cities and the idea of a business centre outside of Paris. Le Corbusier could not convince with his concept, even if from 1969 to 1973 the Montparnasse Tower, a 210m high-rise office building, had been constructed close to the historic site of the Hôtel National des Invalides.

The construction of La Défense in the 1960’s and 1970’s

The first construction in the new business district had been the CNIT (Centre of New Industries and Technologies), built between 1956 and 1958 even before the creation of the EPAD. Its architects were Robert Edouard Camelot, Jean de Mailly, Bernard Zehrfuss accompanied by the engineers Jean Prouvé and Nicolas Esquillan. The building’s roof is a reinforced concrete self-supporting vault of 22500m2, only 6cm thick with a 128m span, which made it a world record. Followed by the first building dedicated only for office spaces in France, the Esso tower delivered in 1963 and offering space for 1500 employees of the oil and gas corporation. The Architects Greber, Lathrop and Douglas designed with this building the first metal curtain wall on a large façade in France. It had been demolished in 1993 and replaced by the project Coeur Défense.1

In 1964, the French State approved a master plan drawn up in 1960 by EPAD and based on a modernist approach, with the separation of the traffic flows through a large elevated platform with an alignment of equal high-rise buildings on both sides. The platform is composed of a central pedestrian plaza and smaller side spaces, while the underground levels contain the services, roads, parking spaces and technical infrastructure. The first generation of towers following this plan was of same size, like the Esso tower: a 42m by 24m base, rising up to 100m height with 30,000m² office area per tower and often grouped in twin towers.

The first master plan drawn up in 1956 by Camelot, De Mailly and Zehrfuss for the candidature of Paris for the Universal Exhibition of 1958 was not based on the elevated plaza or slab concept. It featured a ground-level development structured around the historical axis of Paris. The basic principle of separating traffic flows was adopted later with the concept of an artificial plaza or slab reserved for pedestrians. This concept required very complex engineering processes with considerable investments, but it suited the different requirements of the site: situated on a historical and communication axis, being a place of dense activities and ensuring the comfort of the people who worked and lived there.

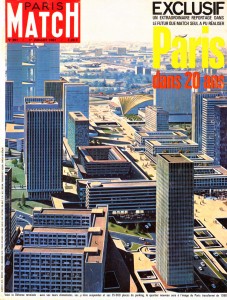

In the 1960’s the construction of La Défense also led to general debate in France. The French weekly magazine Paris Match illustrated, in its edition of July 1967, through different architectural drawings, an image of Paris in 20 years following the example of the new modern urbanism of La Défense.2 In the same year the movie Playtime by the French filmmaker Jacques Tati was released in which he himself plays a character called Monsieur Hulot. In the movie Monsieur Hulot is trying to find his way through a modern and somehow dehumanized futuristic Paris, in reference to the modern architecture of La Défense.3

At the beginning of the 1970‘s, the second generation towers appeared to meet the demand for even larger office spaces. The plan of 1964 was modified to accommodate a total area of 1.5m m². The towers offer more space, sometimes up to 100,000m² such as the Fiat tower (today renamed Areva tower), peaking at 184m with 44 floors. Nonetheless the 1973 economic crisis marked the end of the Glorious Thirty and the strong economic growth of France, and stalled La Défense‘s development.

After the 1970’s struggles, La Défense’s was invigorated by the construction of one the biggest mall in Europe, Les Quatre Temps. The third generation towers emerged, less regulated in their forms than those previously built . The 80’s were the beginning of La Défense’s quest to the West. The Tête Défense competition in 1982 posed a fundamental question about the historical axis: to close the perspective at La Défense or to let it go further? The Danish architect Johan Otto von Spreckelsen chose the second option with his winning idea of a white Grande Arche opened in its centre as a symbol of openness to the world.

Recent developments

The concept of an elevated horizontal slab, which is situated above the road traffic on ground level, has been used in different urban developments in the Paris metropolitan area. Examples are the new town of Cergy-Pontoise or the centre of the municipality of Bobigny, both build or transformed from 1960’s onwards. But also in the city of Paris the concept had been applied in the construction of large housing estates, like Front de Seine in 15th arrondissement the or Les Olympiades in the 13th arrondissement. During the following years the concept did not prove its worth in most cases. The spaces under the slab partly became places of insecurity, the access from the natural ground to the slab was problematic and the pedestrian areas often turned into unpleasant open spaces. In the last years most of these urban developments have undergone major transformations, trying to reduce the presence of the slab, to reconnect the natural and the artificial ground and to merge the different traffic flows.

Due to the ongoing debate about the ‘Grand Paris’ and the restructuring of the Paris metropolitan area, the site of La Défense has influenced more complex relationships. The formerly exclusive dialogue with the central city Paris has turned into a conversation with the multiple local public authorities. The initial urban design is still identifiable and the trademark of the business district. But even if the separation of traffic flows is still functional in the central part, the elevated roads once surrounding La Défense have been brought back to the natural ground and reconnected with the general street grid. Public spaces have been transformed in multi-functional spaces offering diverse uses to pedestrians. Mixture of functions and urban intensity has become a keyword and La Défense tries to create services for the everyday needs of its users. And in a few years the first multi-functional towers of the Russian investor Hermitage might emerge.

La Défense with its particular urban forms is one of the major landmarks of the Paris metropolitan area, easily identifiable. Whereas the concept of the elevated slab applied to housing estates did not stand the test of time, in the case of the dense business district of La Défense it seems to be more appropriate in its central role. Major mistakes had been made in the period from the 1950’s to 1970’s mainly by ignoring the surrounding territory and constructing La Défense in a purely top down decision. But it has to be valued as an urban and architectural experiment with unique constructions and creating a unique urban development. In the 1980s and 1990s the development of the site concentrated on the construction of new high-rise building and neglected the urban scale and public spaces. In recent years the reinforced positions of the local communities has lead to a more balanced dialogue with the French State. There is a chance to correct the errors of the past, and to adapt the urban environment to the contemporary needs while keeping the uniqueness of this urban experiment of the 1960’s.

1 Chabard, Pierre. Lefebvre, Virginie (2013) La Défense : Un dictionnaire

2 Paris dans 20 ans (1st July 1967) Paris Match

3 Playtime (1967)

Bibliography

Chabard, Pierre. Lefebvre, Virginie (2013) La Défense : Un dictionnaire architecture / politique et un atlas histoire / territoire. Marseille : Éditions Parenthèses. 680p. ISBN 978-2-86364-265-8

Collectif (1995) L’urbanisme de dalles, continuités et ruptures : Actes du colloque des Ateliers d’été 1993 de Cergy-Pontoise. Editeur Presses Ecole Nationale Ponts Chaussees. 180p. ISBN 978-2-8597-8245-0

La Défense en quête de sens (December 2008) Revue Urbanisme, Iss. Hors-série N°34. ISSN 0042-1014

Lefebvre, Virginie (2003) Paris, ville moderne. Maine-Montparnasse et La Défense 1950-1975. Paris : Editions Norma. 300p. ISBN 978-2909283784

Paris dans 20 ans (1st July 1967) Paris Match, Iss. N°951. ISSN 0397-1635

Pellegrino, Pierre. (1999) Infrastructures et formes urbaines (Tome 2). Architecture des Réseaux. Paris: Editions L’Harmattan. 216p. ISBN 978-2-7384-7980-4

Playtime (1967) Directed by Jacques Tati. [DVD] France: Specta Films (France), Jolly Films (Italie)

Author: Christian Horn is the head of the architecture and urban planning office RETHINK

The article had been published in the magazine Project Baikal n°39-40

[…] took place in the Pôle Universitaire Léonard de Vinci in the business district La Défense. The place usually hosts an Institute of Internet and Multimedia, an engineering school, and a […]

Hi There,

I am writing to ask if you own the image « View from the shanty towns of Nanterre in front of the CNIT shortly after its construction »?

I am seeking permission to use the image in my PhD thesis on the work of film maker Jacques Tati.

kind regards

Louise

Dear Louise,

Thank you for asking.

I generally try to use my own images, to find images labelled Creative Commons, or those in the public domain.

Concerning the image of the shanty towns of Nanterre, I could not find out who was the author. So I can not help you further on this point.

Best regards, Christian

Thanks Christian

It’s always interesting to see old pictures of the Cnit. Now it’s not the same!

See my report from 2022 on what has become of the Cnit.